Calder and Hebble

The Halifax Arm Part 1

Calder and Hebble The Halifax Arm Part 1

by Alan Briggs

Introduction

My first awareness of the existence of the Halifax arm of the Calder and Hebble canal came in 2005, shortly after I had taken my first boating holiday on the Trent and Mersey canal near Nottingham. I had always had a nostalgic interest in the subject, my early childhood having been spent playing on the locks of the Leeds - Liverpool canal at Apperley Bridge, near Bradford. Little did I realise, at that time in the early fifties, that the occasional passing boats that intruded into my playground were the last of their kind to be seen. The Halifax arm was by this date, well on the way to being totally filled in.

Having a desire to repeat my enjoyable holiday as soon as possible, I was forced by high cost of hiring a narrow boat, to satisfy my needs between holidays with canal literature. Although I was living near Wakefield at this time, I had married a girl from the Halifax area and I knew both locations well. So, the first book I bought on the subject, 'The Calder and Hebble Navigation', by Mike Taylor, suited my requirements perfectly. This excellent publication, with it's superb collection of old photographs and informative text, was a revelation to me of an unknown world. Not least of which was the map at the beginning of the book, showing a branch of the canal right into Halifax.

I had had some vague recollection in the back of my mind, that my late father-in-law had mentioned in conversation, a canal basin near the then Mackintoshes sweet factory, at the bottom end of town.

Having personally driven over the restrictive back lanes from the bottom of Beacon Hill to Siddal and Salterhebble, I was well aware of the nature of the ground, and I'm afraid, at the time I did him the great disservice of thinking that he must have been confused about the facts. The steep sided and narrow wooded enclave which is the route of the Hebble Brook, could surely not be the site of a broad beam canal?

Calder and Hebble buildings in the centre

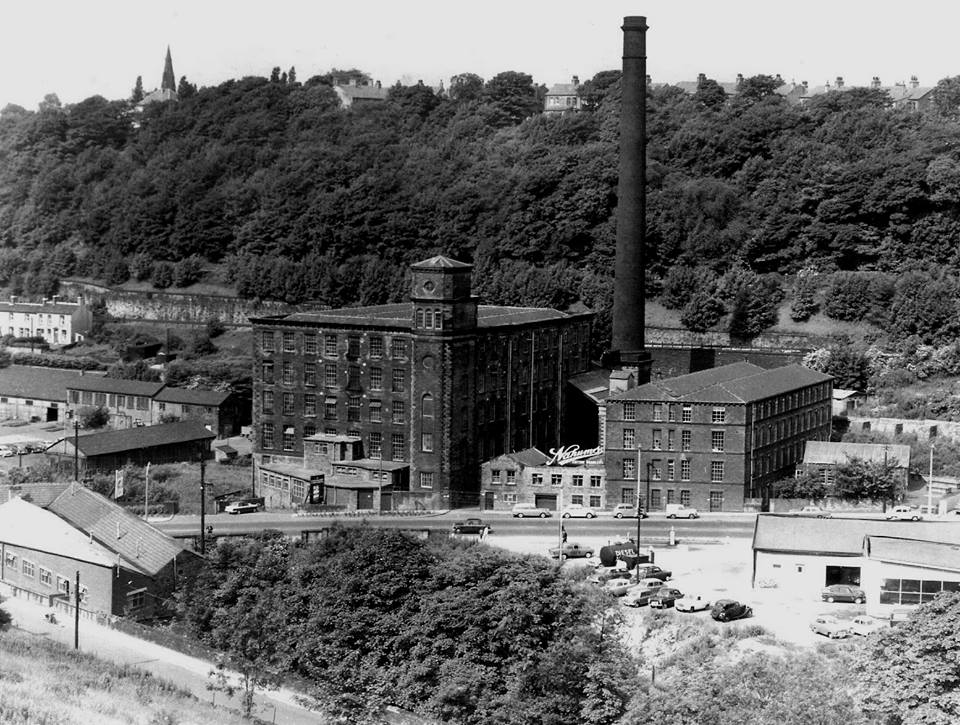

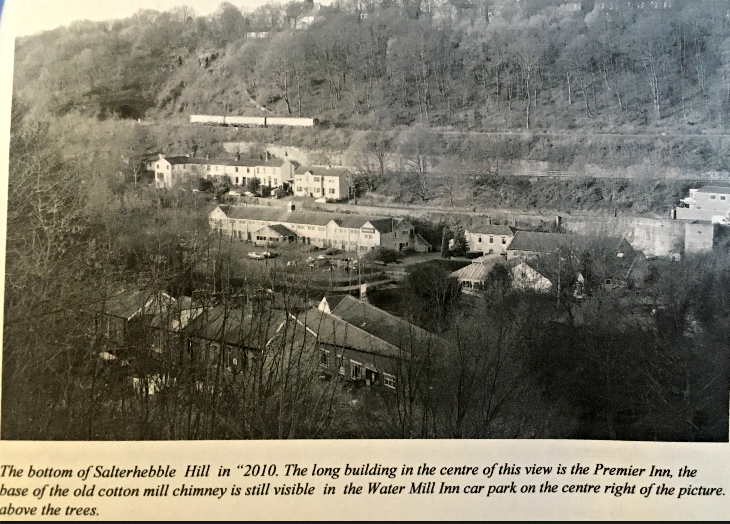

In the summer of 2007, my wife and I visited Halifax and had lunch at the 'Watermill' restaurant at the bottom of Salterhebble hill. The building and it's carpark now occupy the site of a cotton mill which once stood there (Nahums Mill below). A pleasant location overlooking the canal basin, with the remains of the mill still visible on the back wall of the carpark.

After our meal, we walked down to the canal towpath, at the side of the pub, and there, pointing through a road underpass, we saw the sign for the Hebble Trail. My sister-in-law had mentioned the trail to me some time before as a pleasant walk into town. So, we decided to take a short stroll to explore the path.

It was surprising how quickly the impressions of traffic and built up areas gave way almost immediately to a babbling brook in a wooded setting. The path was broad and well surfaced and featured substantially well built walls along the way. However, it was not until we had gone a few hundred metres and were not met with a half buried, but intact bridge in a tree covered depression. that I realised that we were walking the Halifax canal, and these well built walls along the way, were in fact, the tops of buried lock chambers!

My fascination with this remarkable piece of industrial engineering started here.

The opening in 1828 of the Halifax arm of the Calder and Hebble Navigation occurred comparatively late in the canal building boom of the Georian period, although the navigation from Wakefield to Sowerby Bridge had been completed over fifty years before, in late 1770, only a transhipment yard and basin at the bottom of Salterhebble hill was in place to serve the town from the main line, a quarter of a mile further to the South, along the Hebble Brook.

Whether the business communities of Halifax considered that Salterhebble was close enough to meet their needs when the main line navigation was being planned, is unclear. What was certain, was that taking the arm any further into the town involved considerable opposition from the mill owners along the sides of Hebble Brook and to any plan by the Calder and Hebble company for the storing and extraction of water from above their mills for canal use.

The flow of the Hebble was already in great demand for the driving of machinery and processing of materials. This opposition and the considerable engineering problems that needed to be overcome for such a short section of canal, (one and a quarter miles) and the high financial penalties such difficulties would incur, would have been key factors for the canal investors at the time.

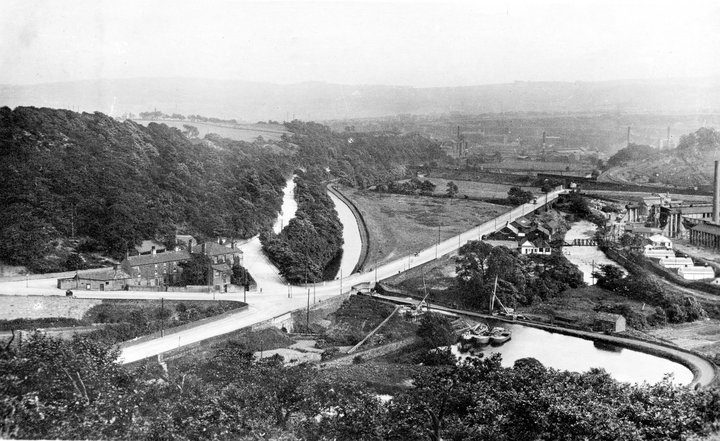

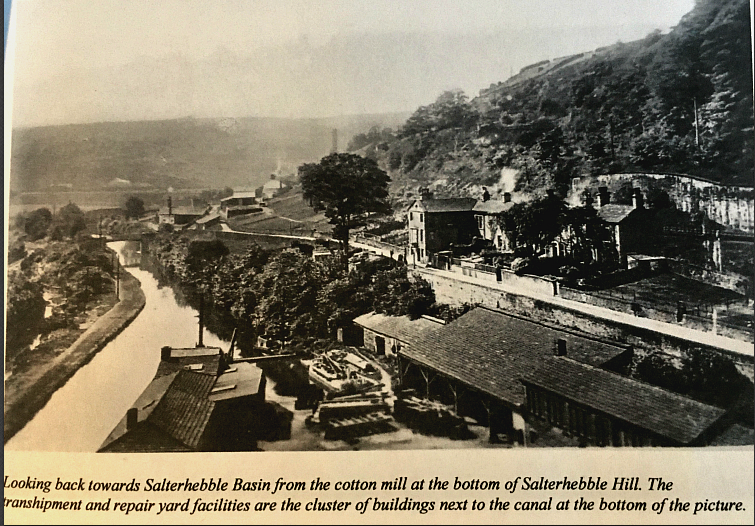

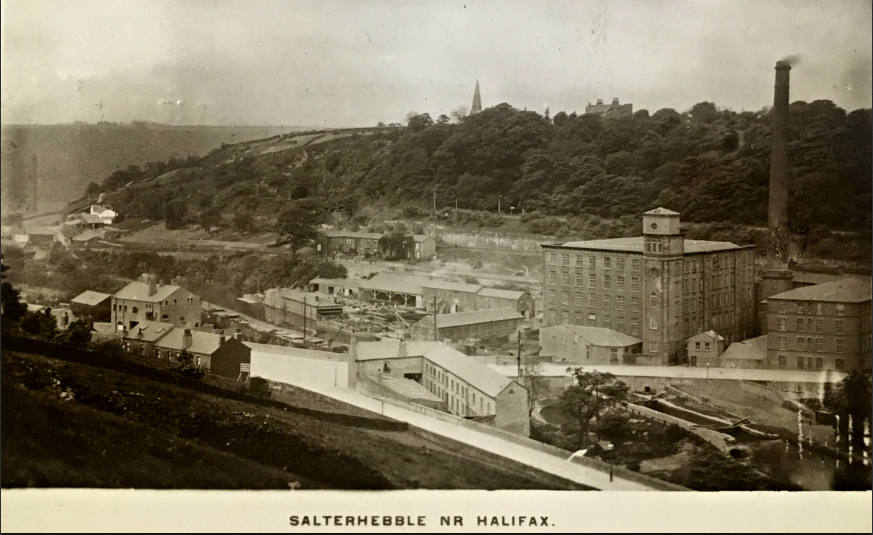

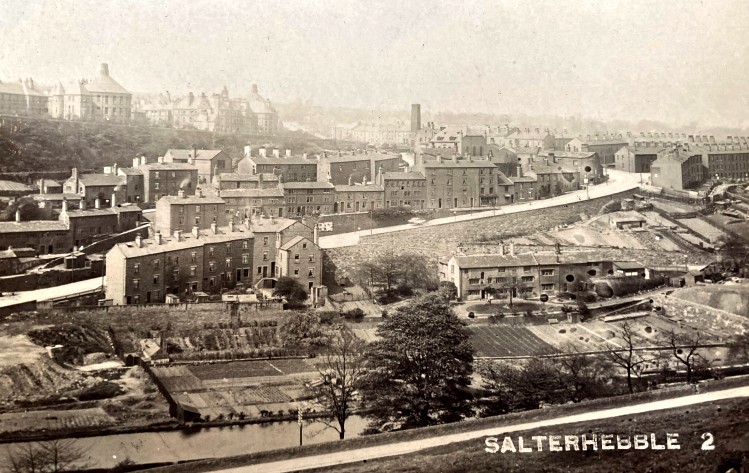

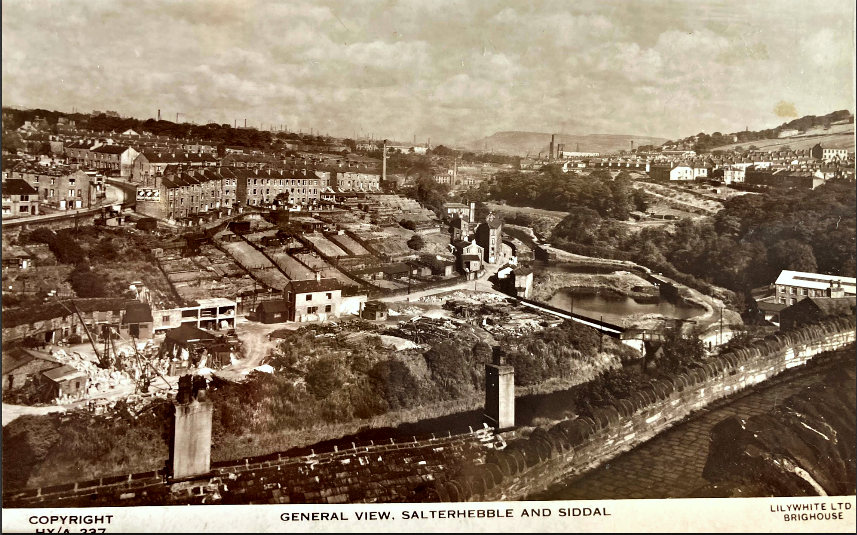

The group of buildings in the centre left of this 1913 picture are the transhipment and repair yard facilities at the bottom of Salterhebble Hill, now the site of the Premier Inn. Number one lock of the Halifax arm is shown in the bottom right of the photograph, the two small reservoirs that fed the Siddal pumping station are behind the trees at the side of the lock.

Dr. J. A. Hargreaves, in his book on Halifax, commented that in the late 18th and the early years of the 19th century, Bradford began to outstrip Halifax in industrial development, especially with the installation of steam engines in it's mills. He noted that Bradford was compelled to move towards steam power at an early stage in it's industrial expansion because of it's poor water resources and richer coal reserves. The industrial revolution that was taking place across the country at the time was only ever about one thing, making money.

It is not surprising therefore, that Halifax had initially clung to it's older technologies for much longer than Bradford. After all, steam engines were expensive items and the coal to keep them running had to be road hauled into the town. The mile and a quarter of broad beam canal that was needed to connect Salterhebble basin to Halifax town centre was never going to be an easy or cheap enterprise. Those investors in the expanding businesses along the Hebble Brook would need some persuading, because as things were, manual labour was cheap and water power cost nowt (sic).

Nevertheless, in the early years of the 19th century it was becoming apparent that Halifax was losing it's position in the industrialisation race that was taking place. The problem for Halifax was that these new steam driven mills required coal in enormous quantities, and the system of distribution from local mines and the Salterhebble transhipment yard could not cope with the demand.

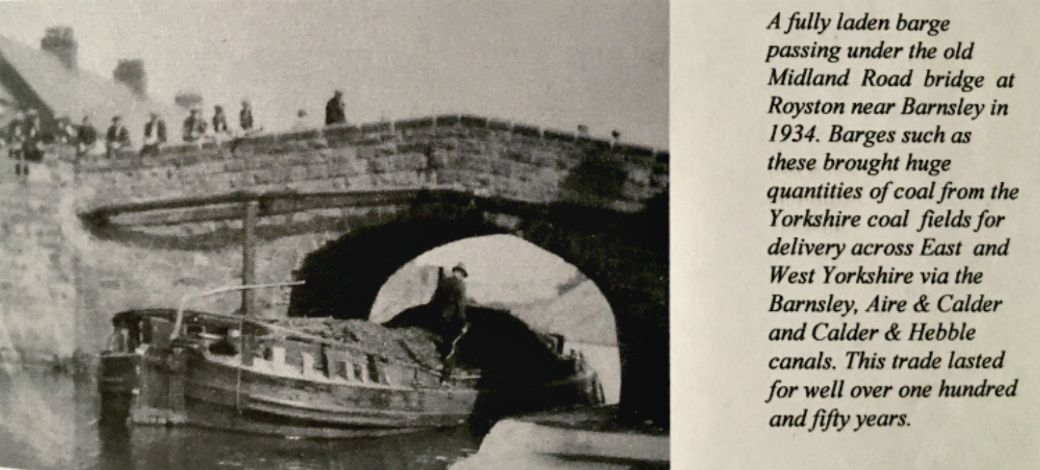

A paired team of man and horse could cart loads of about a ton at a time, although the hills and road conditions of Halifax would have made this a slow and laborious task. The same team could haul loads on water of up to sixty tons per boat. Increasingly, these were the sorts of delivery amounts becoming necessary to meet the demands. In 1828, Anne Lister of Shibden Hall bemoaned the fact in her Journal, that it was cheaper to bring coal from the Kirklees area to Salterhebble by boat, then to road haul it into town from local mines on Swale Moor at the head of the Shibden valley.

In an earlier entry, in 1822, she had complained that it had taken all but two hours in travelling from Bradford because of the state of the roads. The track ways and lanes around Halifax had evolved to serve the needs of the farmers, spinners and hand weavers in order to get their produce, materials and finished articles to and from the trading centres in the town.

Like an ever expanding web, they had spread into the hills around Halifax as the growing population moved further up into the less desirable and least productive marginal lands that were still available to them. These pack horse lanes and tracks had proved adequate for the woollen trade for several hundred years. However, they proved to be most unsuitable in meeting the needs of the new mechanised systems of factory production whisch was slowly being introduced into the district towards the end of the eighteenth century. The first such mill had been established for cotton spinning by Richard Arkwright at Cromford, Derbyshire in 1771. So successful and profitable was the model started by him that it was soon to be replicated for many forms of production across the length and breadth of the country, especially so in the textile trades.

The old bank road out of Halifax over the shoulder of Beacon Hill in 2010. This ancient route was the main access to the east prior to the completion of the turnpike road in 1741, taking the road out of town via North Bridge. Even after the later additions to the old bank of cobbles and stone clad banking, this would have been a difficult and dangerous route for any horse drawn vehicle use.

The new age of steam power was gaining momentum in the area, and if Halifax wished to maintain its' growing prosperity it needed to embrace the trend. Although some textile production techniques continued to use water power well into the second half of the 1800's, the new mass production machinery, which required a smoother and more constant form of power, steadily began to dominate in the district. The uncertainties of the British weather would eventually put an end to the use of water powered mills in the area, their susceptibilities to floods and droughts and the adverse effects that this had on production was losing businesses money.

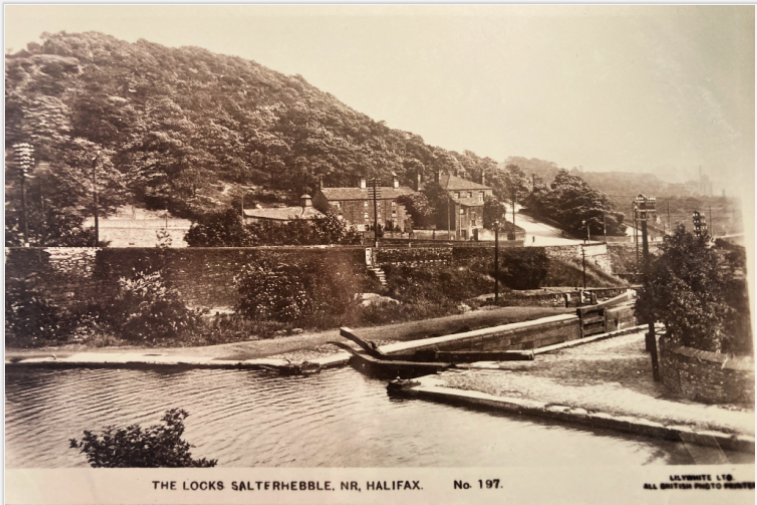

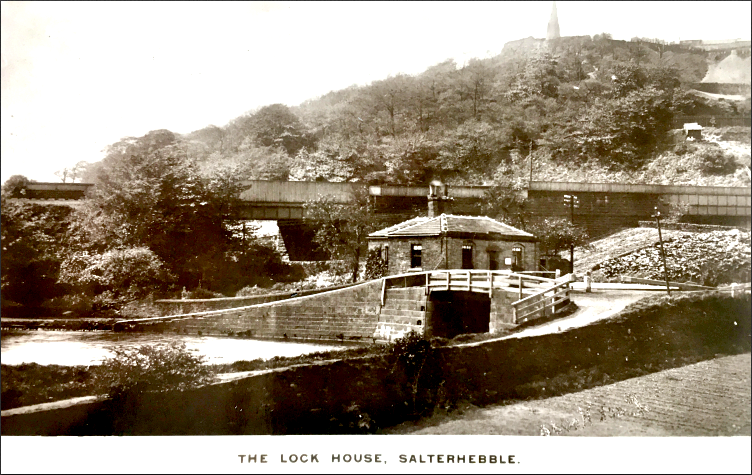

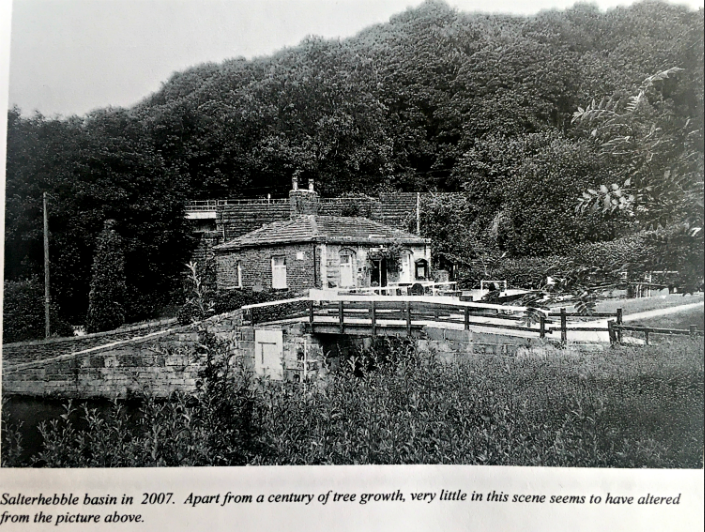

A pre 1914 view of the road up Salterhebble Hill. The picture was taken looking across the canal between locks number 1 and 2.

Same picture with a wider view

The amount needed for the canal extension to Halifax was £50,000, with a further £10,000 before completion three years later. Work started in May of 1825 under the direction of the Calder and Hebble resident engineer Thomas Bradley, with completion in March 1828 to great public acclaim.

The achievement in making a navigable route through the Hebble valley to the town was a true triumph of civil engineering. In the 2,200 or so yards between Salterhebble and the town, the canal lifted boats up through 100ft of height difference by way of 14 locks, under 5 bridges and over a two arch aqueduct, with every drop of water required to run the system being provided from the bottom of the canal arm at Salterhebble.

Salterhebble Bottoms. The canal has all but disappeared under new housing and trees when you view this today, although the Hebble Trail that weaves its' way through the centre of this picture still has numerous relics of the canals' construction on view.

Salterhebble Bottoms in the early 20th century. The curving road in centre left of this picture is Rookery Lane. Also shown are lock numbers 3,4 and 5 with their side ponds between them

The construction of side ponds on sections of canals that climbed steeply with numerous locks, served as a method of water conservation. When a lock chamber is emptied to lower a boat, tens of thousands of gallons of water can be released in a few minutes. If the next lock is very close with only a short and narrow stretch of canal between, the extra volume of released water would spill over the lower gates or round a by wash channel and be lost down the system. The side pond adaptation acts as an expansion area for the released water, which can then be used to fill the lower lock in a controlled manner.

The restriction imposed by the mill owners along the Hebble Brook to supplying water to the canal from almost anywhere along its' entire length, would require an ingenious solution to make the system work at all. The broad locks needed 250 cubic yards of water at each filling to lift or lower boats an average of 7ft 4ins. per lock. Every barge entering or leaving number one lock would lose 42,000 gallons out of the system into the main line navigation. This was a canal that was going to haemorrhage its' most vital asset at an alarming rate, and the engineering solutions needed to be something monumental, which is what they proved to be!

The Hebble brook was dammed with a weir 200 yards up the valley from Salterhebble Road to create an artificial headwater. The accumulated waters was then diverted down a culvert alongside the brook to two storage ponds at the side of number 1 lock. A pumping station was erected 50 yards above the canal level at Siddal. The chosen site at the top of Pheobe Lane was approximately 800 yards from the start of the canal arm. Water was supplied to this pump from the storage ponds, by way of a horizontal tunnel driven from under the ponds, back up the valley to a vertical shaft sunk to meet it from the pumping station. Water was drawn up this shaft by a beam engine and emptied into a second tunnel which fed, by gravity flow, a third storage pond near the end of the canal supplying the terminal basin. Thus creating an artificial circular flow of water of 2 1/2 miles in total.

The water supply system to run this canal was a stunning piece of engineering design. It solved a variety of problems both physical and manmade. The downside was the construction and running costs.

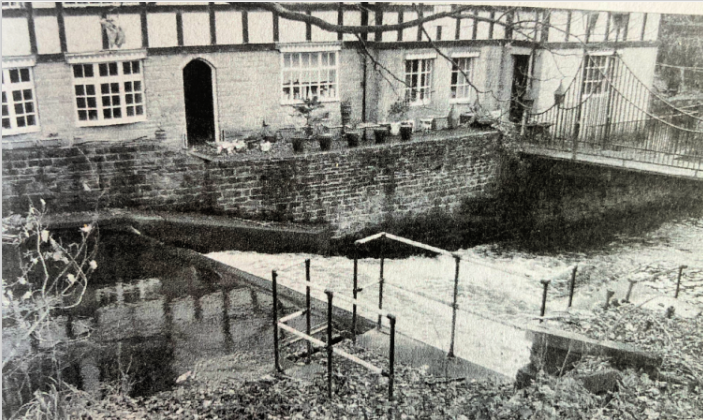

The weir by Myrtle Cottage producing the headwater supply for the canal. The outlet to the supply culvert is centre picture next to the railings

The culvert next to the Hebble Brook flowing under gravity from the weir, 130 yards to the storage ponds, next to number 1 lock.

The two storage ponds at the side of Salterhebble Hill road bridge in 2010. Water ran from here back up the valley for almost half a mile by means of a horizontal tunnel to a shaft sunk from the Siddal pumping station. The Hebble brook is in the top right hand corner of the picture. Behind the wall on the left is the buried remains of number 1 lock.

The pumping station at the top of Phoebe Lane in 2010. With the engine and pump having been removed, it has now been converted into a private dwelling and workshop.

If you have enjoyed your visit to this website, please spread the word by clicking the 'like' and 'share' buttons below. Thank you