Dr. Phylis-Bentley written by Alan Burnett exclusively for www.Halifaxpeople.com

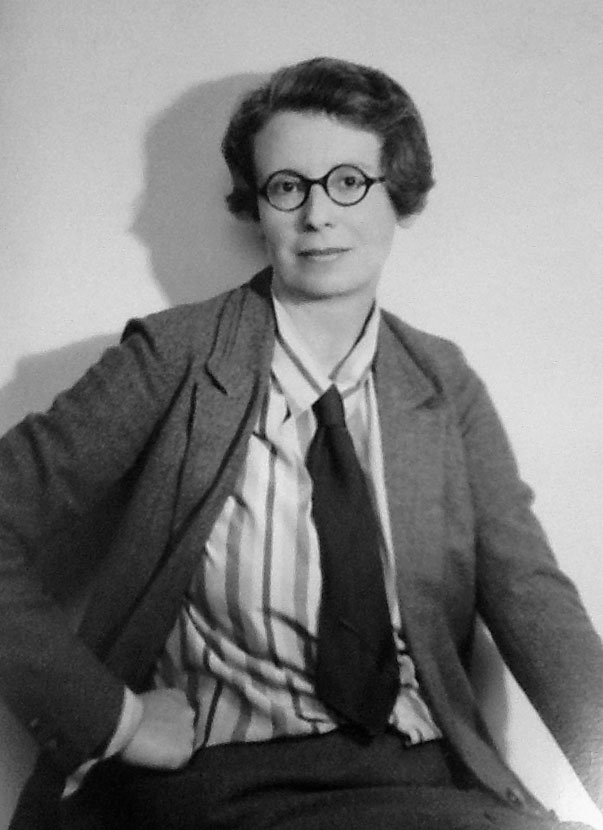

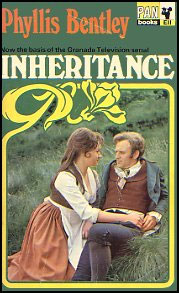

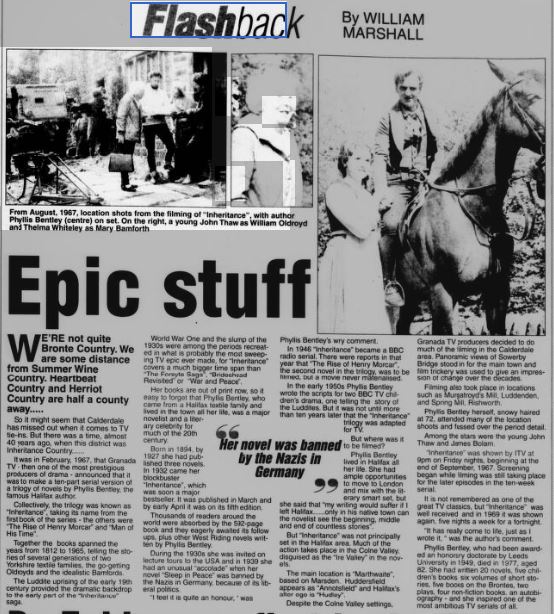

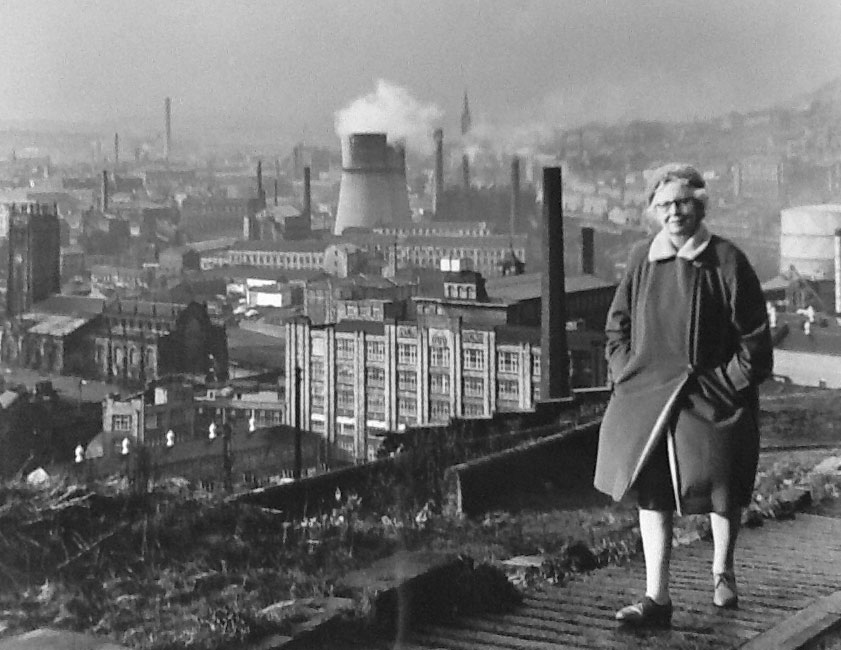

If you stop people on the streets of Halifax and ask them to name a famous Halifax writer you will probably gather a host of puzzled looks. There will be the odd one or two who will offer you Ted Hughes in the hope that you might be prepared to stretch your definition of Halifax, but for the main you will have people flummoxed. Fifty years ago, the challenge was far more likely to lead to a successful outcome and seventy-five years ago you could have extended your trial area to include both sides of the Atlantic and probably received the same answer: Phyllis Bentley. Dr Bentley was a writer with not just a national reputation, but an international one. During a lengthy career she wrote more than twenty books – one at least of which was turned into a hit television series of the 1960s. Her book, “Inheritance” which was published in 1932, received critical acclaim, and during the thirties and the forties she was often called perhaps the finest English regional novelist since Thomas Hardy. But Phyllis Eleanor Bentley O.B.E was not just a writer born in Halifax but one infused with the very essence of the town: as Halifax as Beacon Hill; as Halifax as black clouds over Queensbury; as Halifax as Phyllis Bentley. If ever a famous daughter of the town needed to be remembered in this day and age when writing is compressed into Twitter streams or Blog posts, it is Phyllis Bentley.

Phyllis Bentley was born in November 1894 in Halifax, the fourth child and only daughter of Joseph E Bentley and Eleanor Kettlewell who were both members of long standing West Yorkshire textile manufacturing families. Her father had been a junior partner in a large textile manufacturing undertaking, but had later set up his own woolen textile finishing company at Dunkirk Mills on Parkinson Lane. When she was a child, her mother would tell stories about her own family and, in particular, of her two uncles, Joshua and James Hanson who had come from Huddersfield. It was a typical West Yorkshire story of a powerful family being divided by politics, by art, and by attitudes to what then as now was the driving force of many a Yorkshireman – brass (money). Phyllis’s grandmother’s two brothers had taken two very different paths and it was that partition that Phyllis later claimed was the idea behind her great “Inheritance” trilogy of novels. Joseph had stuck with manufacturing, the very model of a millstone gritty Victorian entrepreneur. James had sought education, become a political radical, started a left wing newspaper and reformed the secondary schools of Bradford.

Whilst Phyllis had

descended from Joshua’s branch of the family, some of that love of words and

learning and some of that radicalism had leached into the warp and weft of her

genetic make-up, for from being a young girl she wanted to write. Her parents

sent her to Halifax High School for Girls but later she transferred to

Cheltenham Ladies College where she took an external London University degree

in English and Mathematics. And so

Phyllis, age 20, with her Yorkshire accent and her embarrassment at what she

felt were her unsophisticated ways, launched herself on the world, determined

to make a name for herself as a young, proud, female, writer. And it was, of course, the summer in which

the world fell into the madness of the Great War. At first Phyllis got herself

a job teaching at a North London school, but hated it. She then got a job at

the Ministry for Munitions and this gave her the satisfaction of believing that

she was making a real contribution to the war effort. Eventually she finished

up back in Halifax, teaching English and Latin at Heath Grammar School, a

stone’s throw away from the house she grew up in.

When the war was over and the soldiers eventually returned from the front and reclaimed their jobs, Phyllis was determined to make her way through life as a writer and in 1918 she published, at her own expence, a volume of short stories, entitled “The World’s Bane”. It met with little success, and neither did the two novels that followed in the early twenties. By the late twenties her hopes of making a living as a novelist seemed to be heading for defeat : her books were not selling, her father had died and the family business was in trouble, and she had to watch some of the sophisticated friends of her youth, such as Vera Brittain, find success in the world. But Phyllis was from Halifax, and Halifax folk find it difficult to give anything up.

The breakthrough came when she signed a contract with the new publishing house of Victor Gollancz, a firm that was about to become one of the literary beacons of the 1930's. In 1932 Gollancz published her novel that charted life in the West Riding over 150 years and intertwined questions of love, class, politics and family loyalty against the background of the industrial revolution. The book was an immediate success with both the critics and the general public. It cemented her reputation as one of the most successful regional novelists of the twentieth century. And the success of the novel led to her becoming in demand as a reviewer, a lecturer, and a radio broadcaster. Her fame was reflected on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean and in 1934 she embarked on the first of several lecture tours of America. Within ten years of almost giving up on her literary ambitions, Phyllis Bentley was an author with a growing reputation.

Phyllis Bentley wrote in the 1960's about how her attitude to Yorkshire and Yorkshire people changed in the early 1930's. Writing about her earlier life she said:

“I was a Yorkshire girl and proud of it. I loved the hills rolling away into the distance, springing out of each other in complex folds which, as it were, smiled sardonically at my efforts to find a word to describe them. I loved the purple heather and the dark rock, the russet bracken, the tumbling streams, the tough pale grass, the rough mortar less walls. Above all I loved the strong west winds, driving the great grey clouds relentlessly across the sky. But I did not love the West Riding people. I was on Great Uncle James’ side, I was an intellectual. Yorkshire people were strong, stubborn, independent folk, yes. I granted them that. But they were often course. They said to me cheerfully, “I haven’t read any of your books”, as if this were a virtue on their part. … They said “Do you make anything by it then?”, “Not much eh?” “Is it worth it then”. For they loved brass”

But her attitude to the people of her town and her county changed when the recession hit and firms went bankrupt and men were laid off. She remembered men coming to the back door of her family house asking for work. She recalled two local manufacturers of her acquaintance who were driven to suicide by the great depression. She writes:

“It was at this time, when the West Riding folk were bowed almost to the earth in defeat, that my heart went out to them. I was their kin, their cause was my cause.”

The connection between Phyllis Bentley and the town of her birth shines through in an article she wrote for a series in the Yorkshire Post in 1935. Entitled “The Yorkshire I Know”, Phyllis Bentley speaks lovingly and admiringly of her native Halifax.

“My Yorkshire was called Halifax and Hebden Bridge, Sowerby Bridge, Norland, Barkisland, Huddersfield, Beacon Hill and Queensbury formed its uttermost boundaries. It was thus entirely occupied by spurs of the Pennine Chain, and those words Pennine Chain were magical ones to me… From my childhood upwards I was extremely proud of the geography and geology of the West Riding, long before I understood its significance in West Riding life. I was proud that my Yorkshire was coloured so richly brown on the map, and felt a genuine pity for children whose birthplaces were merely honey-coloured, or even, poor things, green : to live amidst gradients less exciting than my own seemed feeble. A true patriot, I adored even the inconvenience of my native land. That its contours were dangerous for bicycles, wore out horses, and necessitated numerous tunnels on the railway lines, seemed to me essentially right and proper. I loved to hear how the very tram lines had a narrower guage in Halifax than elsewhere, because it had been thought impossible for any but single-decker trams to dare our preposterously steep streets. …. At night these trams lighted, crawling indomitably their dark appointed hills, traced beautiful changing patterns of diamonds and black velvet; to me they were symbols of that sturdy Yorkshire character I admired so much. Which stood no nonsense from anything, even gradients.”

Other

than that brief period during the Great War, Phyllis Bentley lived all her life

in Halifax. She was a Halifax woman : a founder member of the Thespians, an

active member of the Author’s Circle and the Women’s Luncheon Club, a stalwart

of the Literary and Philosophical Society. She also became a noted expert on the lives of

those near neighbours, the Bronte Sisters, and published an acclaimed biography

of the sisters in 1947. During World War II she once again volunteered her

services, putting her frequent contacts with the United States to good use by

working for the American Division of the Ministry of Information. She opposed

fascism with the radical fervour of her Great Uncle James and claimed great

pride in the fact that her books were banned and burned in Germany by the

Hitler regime.

After the war she continued to write, adding a second and third part to what had now become the Inheritance Trilogy. She also continued to attract honours and awards : receiving an honorary doctorate from Leeds University in 1949, becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1958, and receiving an OBE in 1970. In 1963 she at last moved from the family home in Heath Villas on Free School Lane, but only as far as the village of Warley where she lived out the rest of her life in Warley Grange.

And

so to the test that we are subjecting all the “People of Halifax” to – would

they be the kind of person you would want to share a pint of beer with in the

Old Cock Inn? Here I must declare an interest, because – unlike the other Halifax people in this series – I did once meet Phyllis

Bentley – although it was a cup of tea and cake I shared with her rather than a

pint of beer. I don’t think I managed to work up the courage to speak to her,

other than for a brief introduction after which I joined the others in hanging

on her words. But in the Old Cock, over a pint of Ramsdens, I would make up for

my youthful shyness. There are many things I want to ask her, many subjects I

want her opinions on. We would sit late into the night and talk about books and

hills and politics and life. And then we would make our separate ways home,

buffeted by the wonderful West Yorkshire wind.

Return to Main page from Phylis-Bentley

If you have enjoyed your visit to this website, please spread the word by clicking the 'like' and 'share' buttons below. Thank you